What role does necropsy play in the diagnosis of respiratory diseases in sheep and goats?

It plays a fundamental role because it provides the first indication of where the respiratory problem is going. There are many different respiratory problems in sheep, and if a necropsy is not performed, you can’t make a good diagnosis.

In the case of the respiratory system, the necropsy is very important for guiding us to the diagnosis.

What would be the necropsy protocol for respiratory problems?

It is advisable to consider more than just the thorax. In ruminants, it is important to open up everything: the neck, the larynx, the trachea…

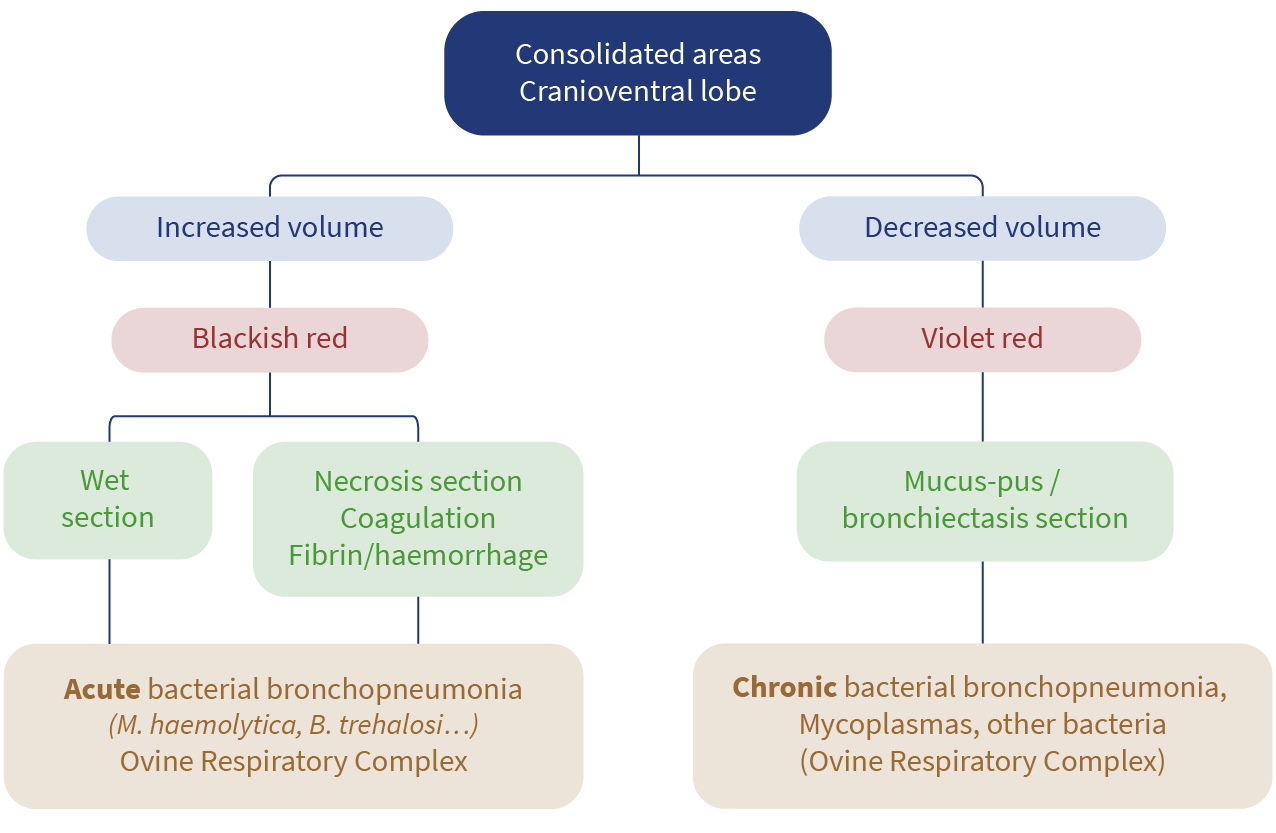

It is imperative to ascertain the volume of the lung within the thoracic cavity. And then open up the head, nostrils and sinuses. And the pharyngeal tonsils and retropharyngeal lymph nodes. And obviously examine the entire lung, especially the right one because it has the cranioventral lobe. It is the most ventral and cranial part in the animal and it has its own specific bronchus, though this bronchus is notably short. It is very easy for bacteria to enter there and it is the one that is most often affected.

Fig. 1. Decision tree according to lesions found in the lung.

Let’s discuss M. Haemolytica. Are there any typical lesions caused by this pathogen?

M. Haemolytica is a somewhat peculiar microorganism in the sense that it is always in the respiratory system and generates toxins, such as leucotoxins, and others.

When the growth rate is gradual, it produces a minimal amount, followed by a milder inflammatory response. But when it grows quickly it generates a lot of leucotoxin, and this is devastating for many structures. For vascular structures, macrophages, neutrophils, which die and release all their enzymatic content into the surrounding areas. And this is what then leads to necrosis and haemorrhage. Furthermore, as they traverse the vessels, they induce vascular alterations, such as hyperaemia and hemorrhages, in other areas.

And there is also Bibersteinia, which “makes its way” through the body and causes sepsis… which also causes lots of other problems.

In terms of lesions, can Mannheimia be distinguished from Bibersteinia?

No, at lesion level, it’s difficult to differentiate between them. It should be noted that although these organisms appear to be found in separate locations, microbiological analysis has demonstrated that they both originate from the lung. However, if we see sepsis lesions on the cadaver accompanied by necrosis and fibrin in tonsils without lung lesions, I would suggest Bibersteinia as first on the list.

There are always bacteria in the lungs, what we call bacterial flora, what happens is that the lung “purifies” them. These bacteria are coming from the nasal passages and go in and out of the lung. In other words, these bacteria are constantly recirculating.

And this can make diagnosis difficult, can’t it?

Yes, that’s sometimes the problem with the diagnosis. In my opinion, samples should always be taken from three areas, if possible: the nasal cavity, the tonsils and the lung.

I recommend those three samples. But of course, sometimes it’s not possible. If I had to choose one, then my advice is to take it from whatever lesion you find. That is, if you find severe rhinitis, then take a sample of the rhinitis. If you find tonsils filled with fibrin, take it from there. Because this means the bacteria has caused damage. Where there is a serious lesion, whether this is in the nasal cavity, the tonsils or the lung, I think that we have to ensure that the sample is taken from there.

Whenever possible, samples should be collected from the nasal cavity, tonsils and lung.

Do you have any recommendations for veterinarians regarding necropsy practices?

Remember I’m a pathologist, and I have no doubts that this is a useful technique. I think veterinarians already practice necropsies quite regularly. But the protocols need to be adapted to something that is less complex, a method that is somewhat easier, to prevent it becoming an inconvenience, and rather something that the veterinarian can perform simply.

In the faculties, we impart protocols that are good for necropsy suites and for giving demonstrations to students. But when you go to a farm you have to change your mindset a little and use different procedures. Normally veterinarians work alone, they do not have anyone with them. For this reason, it is imperative that the approach is practical and to the point.